A Detailed Look At Magic Mushroom History

For such an amazing organism in so many ways, the magic mushroom has in modern times been treated with a lack of respect that borders on blasphemous. For a start there’s the name: Magic Mushroom. It sounds like a supportive character from a Harry Potter movie. Shrooms, mushies, cubes, bald heads and fool’s mushroom – none of them match the grandeur and reverence of the Incas’ "Teonanáctl", which translates to "Flesh of the Gods", the ancient Greek’s "Ambrosia" (Food of the Gods) or the Soma of the Sanskrit Vedas.

Maybe it’s part of a wider disdain for fungi in general. Growing where there’s corruption, decay or cow dung, and warned of their danger from an early age, mycophobia seems hardwired into many cultures. Or maybe it’s part of the media’s tittering association of shrooms with ‘60s hippie excess. They must be delusional...

SHROOM SCIENCE

So let’s begin our look at this most popular of hallucinogens, entheogens, or whatever you prefer to call them, with the scientific and botanical facts! Nearly 150 species from the Kingdom of Fungi have been identified as having psycho effects, the majority of them in the Psilocybe genus, from the Greek words ‘psilos’ (bare) and ‘kub’ (head).

It was only thanks to the accounts of mushroom ceremonies (veladas) in the Oaxaca region of Mexico in the 1950s that pharmaceuticals labs became interested. They discovered the major psychoactive agents in magic mushrooms, and their analogues were synthesized.

The primary active ingredients of all Psilocybe mushrooms are psilocybin and psilocin (and to a lesser extent baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and at least 30 other complex organic molecules found in trace amounts). Psilocin is unstable and it breaks down when the mushroom is dried, while psilocybin lasts much longer (a 115-year old mushroom sample was found to contain some). Psilocybin and psilocin are part of the tryptamine family and bear close resemblance to the neurotransmitter serotonin, and the primary effect, as with LSD, seems to involve its inhibition.

Dr. Franz Vollenweider, of the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland was awarded the first Heffter Award for Outstanding Clinical Research in 1997 for his ground- breaking studies using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to look at brain function of subjects are under the influence of psilocybin. He found that specific brain structures are activated or suppressed during altered states of consciousness.

TRADITIONAL USE

Most knowledge of magic mushroom usage comes from the New World. In Central and Southern America use of psilocybian mushrooms (and other hallucinogens) was common from Palaeolithic times until the arrival of Spaniards, who in the name of the Catholic faith and with liberal use of the sword forbade their use.

Mexico’s ‘Mushroom stones’ - dancing figures wearing mushroom caps - have been dated to 1000-500 BC. Later, the Aztecs had a god for the entheogens, or “inner-god releasing plants” - Xochipilli, Prince of Flowers. He was the divine patron of "the flowery dream" as the Aztecs called their ritual hallucinatory trance.

The Codex Vienna Mixtec manuscript (13th-15th century) depicts the ritual use of teonanácatl by the Mixtec gods. The god known as 7 Flower (his name presented in the pictorial language as seven circles and a flower) was the Mixtec god for hallucinatory plants, especially the divine mushroom, and is depicted with a pair of mushrooms in his hand.

Some Victorian ethnobotanist-explorers such as Richard Evan Schultes wrote about native American use of psychedelic potions and snuffs, and mescaline became popular among a small Western intellectual elite in the early 20th century.

But it was not until 1957 the Wall Street banker Gordon Wasson and his Russian wife Valentina famously documented in Life magazine the existence in Mexico of surviving mushroom cults, initiating the modern search for references elsewhere to their ritual use.

Physical evidence of an Old World mushroom eating past comes from cave rock drawings dating from 10,000 BC in the Tassili Plateau in Saharan Algeria which depict anthropomorphic mushroom beings dancing. Some Northern European rock art depicts various mushroom themes, and Bronze Age vessels have been found decorated with mushroom-related work.

EUROPE’S LOST OR DELETED PAGAN PAST

One of Europe’s leading shroom scholars, Leipzig University’s Jochen Gartz, notes in "Magic Mushrooms Around the World" that it is unlikely that the native cultures of America knew about a large number of natural mind-altering substances compared to Europe and Asia.

The botanical evidence is that there are a similar number of hallucinogenic plants and fungi growing, and it’s unlikely that Europe cultures learned less about local plants and mushrooms than elsewhere in the world. This knowledge was probably lost or destroyed several hundred years ago, Gartz concludes.

He argues that traces of this past are in the tales of ritualistic shroom usage that have spread into myth and legend. Most famously, the Siberian shamans’ use of (red and white) fly agaric mushrooms to enter the spirit world is believed to be the source of the Father Christmas myth.

Gartz also cites Bwyd Ellyon, a magical fungus considered a delicacy in Welsh fairy tales, and the Swedish custom that survives today during summer solstice celebrations of throwing a poisonous mushroom species into bonfires to weaken the power of evil spirits.

Some written reports do survive from the late Middle Ages, all with similar descriptions of psychoactive shrooms as madness inducing. Clusius (1525-1609), a physician and botanist, discovered ‘bolond gomba’, a mushroom known in Germany as Narrenschwamm or Fool's mushroom, which was used in rural areas to concoct a love potion. ‘Fools mushrooms’ were also documented around the same time in Slovakia, Poland, and in England.

Wasson too noted how mushroom usage invariably tends to be euphemized, masked, coded, and buried in etymologies. All lore was oral until the Christian scribes, who may have censored their transcriptions of myths and stories. Wasson believes clues have slipped through.

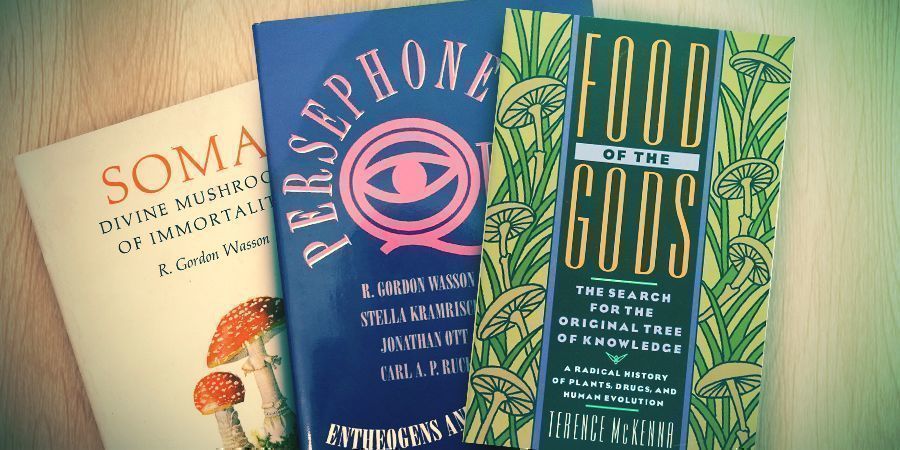

SHROOMS AND THE ROOTS OF RELIGION

Leaning on literary analysis of surviving texts, he argues that the Soma of the Vedic peoples of India included magic mushrooms. In Persephone’s Quest, he goes so far as to say that Mycenaean civilisation began with a mushroom trip, being an ingredient of the Ambrosia of Dionysus. Porphyrius, the 4th century poet, referred to magic mushrooms as ‘children of the gods’, their consumption being a quasi-cannibalistic act that unlocked one's power to experience the divine.

There was an ideological power stuggle between remnants of paganism and Christianity that resulted in aggressive repression and eradication of pre-Christian customs. In the 1970s, John Allegro, a member of the original team researching the Dead Sea scrolls was consigned to academic obscurity for suggesting that the origin of Christianity lay in a middle-eastern mushroom cult.

More recently, respected ethno-botanist Terrence McKenna has posited that mushroom spores may have drifted through interstellar space to Earth, where they have co-evolved with humans to the extent of boot-strapping our intelligence, especially our linguistic and spiritual development.

Today, we are arguably in the endgame of an historical, socio-political climate biased against hallucinogens, in which mind-altering substances have been lumped together and outlawed, whether for scientific research, spiritual use or “mindless” pleasure.

SO WHAT ARE THESE EFFECTS?

Talking of mindless pleasure… Much of the mushroom experience is ineffable, meaning hard to put into words, but here goes. It tends to take 15-30 minutes for the first hints to be felt after consuming shrooms: a warm, melting feeling, sudden bursts of immoderate laughter that can rise to near hysteria at times.

A childlike wonder may descend on you as visual perception becomes fresh or pure, body movements feel more elastic, visualisation behind the eyes is easy, straight lines seem to ripple, and there can be strong emotional identification with people and animals/plants. There is enhanced sensitivity to rythym, music and dance.

Thoughts seem to occur on more than one 'level' instantaneously. The linear nature of ordinary thought is replaced by a more holistic, intuitive "holographic" approach to understanding reality, many observers comparing the state to dreams and other brain functions.

Shrooms are more visionary and metaphysical than LSD, deeper and gloomier say some, friendlier say others, not as fierce in exposing possible traumas hidden. For these emotional reasons, creating a cautious and protective setting is recommended, coupled with positive internal mood primed by careful preparation (setting and set).

Stanislav Grof in the 1950s annalyzed 5,000 LSD protocols to try and identify absolute symptoms that were reported to occur all of the time - and failed. According to him, hallucinogenic substances are "non-specific triggers causing a sequence of altered states of consciousness, which do not form the syndrome labelled toxis psychosis. Rather it is the individual's personality, along with setting that significantly shape the nature of the experience.”

High psilocybin dosage can cause initial painful delirium, with resistance to dealing with conflicts that emerge, but which are resolved through intense psycholytic catharsis. Such an experience may be termed a "bad trip'" by outsiders, but is often enlightening and illuminating to the consumer. The experience produces similar reactions to Grof's LSD therapy: go through hell, prior to reintegration of the personality at a higher level of consciousness.

POPULARISATION: HIPPIE PICKERS

Back in the day, the only way to deliberately get hold of magic mushrooms - without going to Mexico - was to go out to a likely looking field with an experienced picker to show you what they looked like and gather your own. In Europe, “they” were the tiny and powerful Psilocybe semilanceata; known as Liberty Caps in the UK, due to their nippled head looking like the caps worn by French revolutionaries. It was not until 1963 that Albert Hofman and R. Heim proved that P. semilanceata contained psilocybin, like the Mexican mushrooms.

The Liberty Cap soon established itself as the most popular psychotropic species in Europe, maybe even the world. It grows up to 5,000 ft from Finland and Scandinavia to Eastern Europe, the British Isles, Italy and Spain. It’s uniquely easy to identify, with no need for microscopic examination, thanks to its distinctive bell-shaped head.

The species flourishes most abundantly on wet pastures surrounded by forest, fruiting from late September through October, favouring acidic soil and grassy terrain, and clustered in small groups. Animal dung is often found nearby, but they do not grow directly in it, nor do they grow in areas where artificial fertiliser has been used.

Although psilocin and psilocybin were considered Class A drugs in Britain under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act (passed to conform with the UN’s 1971 Convention of Psychotropic Substances), the gathering and possession of fresh mushrooms had never been an offence. The hippie underground was small and discrete enough for modern shroom usage to gradually take off via word of mouth.

END OF THE AGE OF INNOCENCE

Mushrooms first caught British public attention in 1976 when one Judge Blomefield of the High Court handed down a Not Guilty verdict to a man arrested for possession of fresh liberty caps. The courts had ruled that mushrooms that have been dried or "altered by the hand of man" do constitute a class A drug, but Judge Blomefield pointed out famously that: "Psylocybin is a chemical and mushrooms are mushrooms."

In September of the same year, New Scientist carried the first scientific European journal entry about magic mushrooms, and in 1978, researcher C. Hyde reported cases of voluntary intoxication, noting that use of shrooms was “well-known within the hippie subculture of Manchester”.

Other hippie subcultures in mainland Europe picked up on this free, eco-consciousness promoting gift of nature for their own voluntary intoxication. But shroom use never became more than a very minority pursuit, and remained more or less static from the 1950s to the 1990s.

THE MODERN ERA – FARMING & PROHIBITION

And so things remained until the mid-1990s when reliable, economically viable methods of mass production of various strains of Mexican Psilocybe cubensis was developed in the Netherlands. Perhaps because liberty caps are so hard to get hold of in the intensively farmed and fertilised pastures of Holland, but certainly thanks to the country’s existing expertise in market gardening and mushroom farming, the country became the centre of the new, fresh Mexican mushroom industry.

Starting in Amsterdam, ‘psychedelicatessens’ or headshops began stocking a range of cultivated shrooms; Mexican, Hawaiian, etc, and later Philosopher’s Stones, the knobbly sclerotia that grow underneath the P. tampanensis species. For a while they got away with it, registering as greengrocers, subject to fresh vegetable laws. A thriving export market developed, most notably to the UK.

At the peak of the shroom boom in the early 2000s, the Netherlands had 120-150 shops selling mushrooms, around half of them in Amsterdam. The UK had 300 market stalls and shops selling them. Sooner or later the tabloid press waded in with scare stories. Some teenager gets themselves in trouble and bingo, end of the party.

One by one, the EU countries began banning the sale of cultivated and picking of wild magic mushrooms; Denmark (2001), the Netherlands (2002), Germany, Estonia and the UK (2005) and Ireland (2006). Japan, which has its own unique history of Shinto-influenced natural shroom spirituality, also banned their use (2002). In some territories it is ok to sell fresh magic truffles (scelrotia) and to buy and use mushroom growing kits and spores.

HEALTH

Psilocybin mushrooms have low toxicity - in tests with mice in the ‘50s, doses up to 200 mg of psilocybin/kg of body weight have been injected intravenously without lethal effects. The LD50 is 280mg/kg body weight, while effects appear at 0.02 mg/kg in humans. To experience any toxic problems, you would basically need to eat your own bodyweight in shrooms, says researcher Jonathan Ott.

As for mental problems, psychedelic pioneer Stanislav Grof encountered two psychotic episodes in over 3,000 sessions, and these were back to normal in a couple of days. Yes, there can be and are existential problems created by the novel experiences brought about by mushroom use, but it is precisely this catalytic effect that committed psychonauts welcome.

THE REAL THREAT OF SHROOMS

Many believe the problem with magic mushrooms from an authority perspective is not one of public health but that the content of the mystical experience is inconsistent with both the religious and secular concepts of traditional Western thought. Moreover, mystical experiences often result in attitudes that threaten the authority, not only of established churches, but also of secular society.

“Unafraid of death and deficient in worldly ambition,” said psychedelic pioneer Alan Watts over 40 years ago, “those who have undergone mystical experiences are impervious to threats and promises. Moreover, their sense of the relativity of good and evil arouses the suspicion that they lack both conscience and respect for law.”

Happening all oll over the Western world, the explosion of interest in yoga, vedanta, zen buddhism, and the chemical mysticism of psychedelic drugs prompted Watt to believe that “the whole ‘hip’ subculture, however misguided in some of its manifestations, is the earnest and responsible effort of young people to correct the self-destroying course of industrial civilisation.” But of course, those with their hands on the wheel of industrial civilisation don’t want its course correcting, so its easier to just ban mushroom use.

PROMISE FOR THE FUTURE

Psilocybin, mescaline and even LSD had once been a respectable part of upper-class intellectual life; anthropologists and scientists, artists and writers such as Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary wrote enthusiastic accounts of the marvellous potential of these ‘trips’; the media gave sympathetic coverage of these newly-discovered substances.

But as the stuffy ‘50s rolled into the dynamic ‘60s, psychedelics played a key role in rise of the environmental movement and opposition to the consequences of economic growth; modern feminism and massive apposition to the war being fought in South East Asia.

The gentlemen scholars watched as their new tools for self-realisation and mind exploration were casually used at rock concerts by anyone who felt like it; Hell’s Angels and Peaceniks, students and hipster businessmen. Governments banned the use of psychedelics in any kind of context, street or university.

“It would be a tragedy if research in to these fascinating substances,” said David Nichols of Purdue University Medicinal Chemistry, “that relate to the process of dreaming, consciousness, and spiritual revelation, and how we perceive the environment we live in and who we are - the basic questions of 'what is man?’ were to be allowed to fizzle out. These facts alone should stimulate research, and urge psychology, chemistry, and related fields to collaborate.”

SHROOMS AS A TOOL OF THE SACRED

For whatever reasons, there are signs of positive change 20 years later. There’s activity once more in the academic research field, with licenses being quietly granted for work on ecstasy, psilocybin, ayahuasca and the African psychedelic, Ibogaine, to the extent that there was talk of an 'Entheogenic Revival'.

Shroom awareness grew considerably in the 1990s. Terrence McKenna is probably the one person who has done most boost this awareness with his “Food of the Gods” ideas - making the connection between the ancient tribes for whom mushrooms were central to their nomadic existence - and the modern day neo-tribalism of ravers, eco-activists, and urban shamans.

The split between ‘proper’ academic research and public usage enforced by the USA’s Federal Drug Administration in the early 70s is healing, partly thanks to the gradual recognition of the huge theoretical and practical value of “underground” research.

Conventional neuroscience, as increasingly sophisticated probes, scanners and markers have been developed, is discovering just how many “drugs” or substances very similar, are found naturally in the brain. The fact is, drug “tools” offer another important piece of the mind-brain jigsaw puzzle that has occupied scientists and philosophers for centuries, and many serious researchers are aware of this, and may even have utilised them themselves.

SHROOMS AND THE GAIAN MIND

Let’s leave the final word on the potential of mushrooms to Paul Stamets, probably the greatest mycologist of our age. “Covering most landmasses on the planet, and indeed floating in the oceans, are huge masses of fine filaments of living cells from Fungi, an entire kingdom of life barely explored,” he says.

“More than a mile of these filaments (called mycelia) can permeate a single cubic inch of soil. Fungal mats have been identified as the largest biological entities on earth, with some individual mats covering more than 20,000 acres. In full growth, the mats can grow outwards at up to two-inches day. Every ounce of forest soil contains thousands of species of fungi. Of the estimated 6,000,000 species, barely 50,000 have been catalogued.”

With their dense interconnections, Stammets believes mycelia are “earth’s natural Internet, the essential wiring of the Gaian consciousness.” Now that’s something to contemplate next time you’re shrooming!

You might also like

United States

United States